Report of the Committee of Enquiry into Farm Attacks, 31 July 2003

- 00: Table of Contents (PDF)

- 01: The Appointment of the Committee (PDF)

- 02: Incidence and Nature of Farm Attacks (PDF)

- 03: Examples of Farm Attacks (PDF)

- 04: Case Studies: Direct Attacks (PDF)

- 05: Case Studies: Land Invasions (PDF)

- 06: Victims of Farm Attacks (PDF)

- 07: Perpetrators of Farm Attacks (PDF)

- 08: Investigating Officers and Prosecutors (PDF)

- 09: Submissions to the Committee (PDF)

- 10: Literature Review (PDF)

- 11: The Farming Community (PDF)

- 12: Crime and Its Causes in South Africa (PDF)

- 13: The Criminal Justice System and Farm Protection (PDF)

- 14: Comparative Studies (PDF)

- 15: Legislation on Land and Land Reform (PDF)

- 16: Security on Farms and Smallholdings (PDF)

- 17: Trauma and its Treatment (PDF)

- 18: Conclusions and Recommendations (PDF)

- 19: Summary of the Report (PDF)

- 20: Oral and Written Submissions and Bibliography (PDF)

Report of the Committee of Enquiry into Farm Attacks

31 July 2003

COMPARATIVE STUDIES

INTRODUCTION

Farm Murders in South Africa (Carte Blanche 1/2) Farm Murders in South Africa (Carte Blanche 2/2) |

It is alleged by various individuals and groups that farm attacks are unique. It is said that crimes committed during the course of farm attacks differ from other violent crimes in that they are often, and even mostly, politically inspired. The phenomenon is seen as part of an orchestrated campaign to drive the (white) farmers off the land so that the (black) landless people can occupy it. Another perception is that there is a racial undertone to the attacks, which is born out by the fact that farm attacks generally are particularly violent and that the victims are often gratuitously killed or seriously injured.

It would therefore be very useful to compare crimes of farm attacks to other similar types of crimes affecting the physical integrity of the victims. As indicated above, there is no such crime as a farm attack.1 The greater majority of farm attacks are usually manifestations of the crime of robbery or of housebreaking with intent to rob and robbery, usually with aggravating circumstances. Often it is accompanied by other crimes such as murder or attempted murder, rape, etc. The Committee therefore thought that it might be instructive to compare farm attacks with other types of robbery or housebreaking with intent to rob and robbery and eventually the Committee decided to focus on two types of robberies, viz. cash-in-transit robberies and robberies on residential premises (house robberies) in an urban environment.

CASH- IN-TRANSIT ROBBERIES

Cash-in-transit robberies (or CIT’s, as they are known in the banking industry) are classic examples of robbery with aggravating circumstances or, as it is commonly known, armed robbery. There are almost always firearms involved and they are reputedly very violent, often resulting in serious injuries and fatalities. CIT robberies are priority crimes: they are reported to NOCOC in the daily crime report. Unfortunately the figures are for operational purposes only and therefore not totally accurate.2 However, the Banking Council of South Africa also keeps record of CIT robberies, and they are more complete. Although the Council’s security desk also emphasizes that their figures are not completely accurate either, they have made them available to the Committee. (See Table 34)

During 2000 there were 906 farm attacks, resulting in 454 injured persons3 and 144 deaths. Expressed as a percentage of the number of incidents, therefore, there was an injury rate of 50.1% and a death rate of 15.9%. According to the Banking Council there were some 530 incidents of CIT robberies during 2000, resulting in 178 injuries (at a rate of 33.6%) and 25 deaths (at a rate of 4.7%). During 2001 there were 1011 farm attacks resulting in 484 injuries (47.9%) and 147 deaths (14.5%), while in the 505 incidents of CIT robberies 205 injuries (40.6%) and 30 deaths 5.9%) ensued.

During both years the rate of injuries and deaths occurring during farms attacks was therefore noticeably higher than that for CIT robberies, In fact, it is noteworthy that the rate of killings for farm attacks was more than twice as high as for CIT robberies.

If the comparison is made in terms of the number of victims, the difference between farm attacks and CIT robberies is even more pronounced. In the 1011 farm attacks during 2001 there were a total of 1398 victims, with an average of 1.38 victim per incident. Unfortunately there are no statistics available on the exact number of victims involved in cash in transit robberies. According to the head of the Serious and Violent Offences Unit, however, the pattern of CIT robberies is fairly constant.4 There are usually either two, four or six victims involved in each incident, occupying the armoured vehicle and one or two escort vehicles. It is very seldom that there are fewer than two victims and the average number of victims is estimated to be at least three. One therefore has to assume that in the 375 CIT robbery cases there were at least 1125 victims.

Calculated in terms of the number of victims involved, of the 1398 victims of farm attacks during 2001 some 484 or 34.6% were injured and 147 or 10.5 % killed. Of the 1125 victims of CIT robberies, some 163 or 14.5% were injured and 39 or 3.5% killed. This means that the chances of a victim of a farm attack being injured was more than twice and of being killed three times as high as for a victim of a CIT robbery. (Unfortunately the total number of victims involved in farm attacks during 2000 is not known and it therefore is not possible to make a comparison for that year. There is no reason to suspect, however, that the pattern would have varied markedly.)

This difference between farm attacks and CIT robberies is startling. It should be born in mind that the victims in CIT robberies are always well armed and well trained. They are never alone; they are often escorted by armed support; and they are always in immediate radio contact with their head-office and the police. They are therefore extremely dangerous targets for robbers and the latter will definitely know that they cannot give their victims any chance whatsoever. One would therefore expect them to be ready to “kill or be killed”. The attackers are also well armed, often with heavy automatic weaponry. The gangs typically are much larger than those involved in farm attacks, usually numbering between three and six members, but not infrequently more than ten.

Farm Murders in South Africa - SkyNews Min. of Safety and Security: Charles Ngakula: 'If you don't like the crime, leave the country' |

The question therefore arises why fewer victims are harmed and killed in CIT robberies than in farm attacks, where the victims are often alone and quite helpless. The obvious explanation that comes to mind is that the farm attacker assaults his victim with a political or racial motive, rather than merely to subdue him or her with a view to carrying out the robbery. However, a little thought will show that there may also be other reasons that are not so obvious.

- The first is that the CIT attacks are invariably extremely well planned – much more so than the average farm attack. The allegation is often made that farm attacks are carried out with “military precision”. In fact that is not so: investigating officer after investigating officer avers that most farm attacks are carried out in a haphazard way, even if it is preceded by reconnaissance and some planning. That is also borne out by the evidence in most of the court cases.

- TIC robbers are usually either very experienced themselves or else accompanied by experienced associates. They often have previous convictions for similar offences. They often had military training and know how to handle themselves and their weapons in crisis situations. On the other hand, farm attackers are often, though not always, rank amateurs. They are often very young and, in spite of the bravado, they are nervous and afraid. They tend to act irrationally at the slightest provocation. There are many examples of cases where the farm attackers were obviously not acquainted with firearms.

- TIC robbers are usually gangs operating in large groups. They simply overwhelm their victims, who quickly realise that they have no chance to resist effectively. Farm attackers, on the other hand, usually operate in much smaller groups and even alone. They may feel that they are unable to control the victims and at the same time steal what they have come for.

- The TIC robbers always have their escape well planned. They have separate get-away vehicles and planned escape routes. They also know that the alarm has already been raised by radio and that killing the victims will not assist them. This is not the case with most farm attackers. They are usually on foot and sometimes rely on the farmer’s vehicle to escape. Because of the relative remoteness of the farm they need time to escape. They also have to disable the victims so that they cannot raise the alarm too quickly. This they may do by seriously harming or killing the victims.

- The victims of TIC robberies are well trained, not only in protecting themselves, but also on how to handle the situation once they have been overpowered. They know they should not be aggressive or upset the attackers in any way. This training is totally lacking in most farm attack victims, who often put up resistance in a helpless situation. Both investigating officers and state advocates refer to cases where the victims became aggressive and even abusive towards the attackers. (There are also many examples, however, where the victims were totally helpless and submissive, and nevertheless were injured or even killed.)

Finally, it should also be mentioned that cash-in-transit robberies decreased from 530 in 2000 to 503 in 2001. According to the Banking Council the number dropped dramatically to 441 incidents in 2002, although the number of injuries and deaths remained about the same. This decrease may be the result of improved security measures. At the same time it should be noted that the proportion of casualties (injuries and deaths) are increasing, perhaps indicating that CIT robberies are becoming more violent.

HOUSE ROBBERIES IN URBAN AREAS

As is the case with farm attacks, there is no such offence as a house robbery. The term is conveniently used to describe a robbery attack on residential premises. Henceforth it will be used specifically to denote a robbery attack on a house in an urban environment. Like farm attacks, it is usually manifestation of the crime of robbery or of housebreaking with intent to rob and robbery, often with aggravating circumstances. It would therefore be an ideal basis for a comparative study. Unfortunately it has proved to be extremely difficult to obtain the information needed for such a study. The biggest problem was that the necessary information could not simply be extracted by the Crime Information Analysis Centre (CIAC) from their computerised database. The Committee also approached the Serious and Violent Crime Units of SAPS, but they too did not have the information readily available. It turned out that a manual docket analysis of all dockets relating to such crimes would be required for such a study, which would be extremely time-consuming.

Late in 2002, however, Sen. Supt. L. Watermeyer from the national CIAC office led a research study into house robberies for completely another purpose. They examined almost a thousand case dockets of house robberies in all nine provinces and extracted the necessary information. This entailed, firstly, drawing up a list of cases of house robberies from the computerised Crime Administration System (CAS), and then physically perusing those dockets and extracting the required information from them.

They encountered two serious problems. Firstly, it would have been too disruptive if the CIAC researchers were to take dockets away for perusal where the cases were still under investigation or where the court process had not been completed. This meant that only dockets that had been closed, e.g. because the court case had been finalised or it had not been possible to trace the accused, could be used in the research. It was therefore decided by CIAC to limit the research to case dockets which had been finalised during the course of 2001.

The second and equally serious problem was that, although ideally all crimes committed during an incident for which a case docket is opened should be registered on the CAS, in practice very often only the main or most serious offence is registered. This means, for example, that when a murder or a rape is committed during the course of a house robbery, the incident would be registered as murder or rape only, without referring to the robbery.

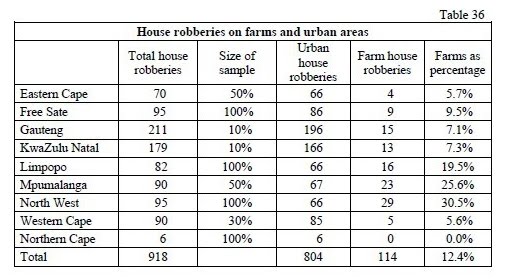

The field team took statistically random samples of various sizes, depending on the total number of cases in the particular province. The total number of dockets analysed came to 918. However, the statistics gathered were not quite in the format that the Committee needed to make a valid comparison with farm attacks, because the dockets included many cases of house robberies that had occurred on farms (i.e. farm attacks). At the request of the Committee the CIAC office agreed to recalculate all the statistics so as to distinguish between farms and urban areas, based on the specific location of the house in question. (See Table 36.) This they did in respect of the Eastern Cape, Free State, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West Province. Some 351 dockets from those five provinces were analysed and the Committee wishes to express its appreciation for that.

CIAC made its first report – covering the Eastern Cape Province – available to the Committee at the end of 2002. The analysis covered some 66 dockets. Of those 80.3% dated from either the year 2000 or 2001, while the others were a few years older. Of the 66 cases 66.7% emanated from townships (with presumably mainly black residents), 19.7% from suburbs and other residential areas (presumably with mainly white residents) and 13.6% from informal settlements (presumably with mainly black residents).

The Committee itself then analysed farm attacks in the Eastern Cape to extract cases suitable for a comparative study, because obviously the Committee could consider only farm attacks where the conditions were similar to those obtaining in the house robberies. It would have been impossible for the Committee to peruse all the farm attack dockets physically. It therefore decided to make use of the NOCOC database which, for reasons set out above5, may contain some inaccuracies. By co-incidence, however, the provincial office of CIAC in the Eastern Cape had a very detailed record of all farm attacks dating from 1994, and much of the information used in this study has been verified directly with that office. The Committee also had access to a memorandum compiled by Supt. V. Nel and Capt. J. Olivier with some comparative figures for farm attacks during 1999, 2000 and 2001.

In the light of what was said above, therefore, the following adjustments had to be made:

- Because eighty percent of the finalised dockets of house robberies looked at dated from 2000 and 2001, the Committee decided to use only cases of farm attacks which had occurred during the same two years.

- Because cases where murder or rape had been committed during the course of the house robbery were not included in the survey, all farm attacks where persons had been killed or raped were also excluded. (In reality 24 persons were murdered in farm attacks during 2000 and 2001, while only one was raped.) However, the house robberies investigated did include one case of attempted rape, and the farm attacks used for this comparison included two cases of attempted rape.

- Farm attacks where the culprit had not entered the house or attempted to do so, e.g. where a resident on a farm had been assaulted or robbed in the veld or away from his or her home, were ignored. Because the house robberies did not cover robberies at businesses, attacks on farm stalls and farm shops were also excluded, even if in the immediate vicinity of the homestead on the farm.

After taking the above into consideration, of the approximately 147 cases of farm attacks that occurred in the Eastern Cape during 2000 and 2001, only some 91 remained which could be used in the comparative study with house robberies. Nevertheless, the Committee believes that the sample is statistically suitable in terms of size and type for a valid comparison. There are certain minor variables which will be pointed out when the specific criteria for comparison are discussed below.

It is a pity that the Committee has not had enough time to analyse farm attacks in some of the other provinces as well. At the request of the Committee, however, CIAC agreed to make a comparative study between house robberies on farms and those in urban areas based on the data they had collected in their docket analysis. This study was limited to the four provinces with the highest proportion of house robberies on farms, viz. Free State, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and North West (See table ??.), and the Eastern Cape was excluded because CIAC’s sample only included four dockets emanating from the farms.) Those provinces accounted for a total of 362 cases, of which 21.3% came from farms. The results of the study were made available to the Committee late in February 2003.

Although the statistics for the farm attacks in the four provinces are included in the discussion below, the Committee has some reservations about the validity of the data. The reason for this is the relatively small sample of house robberies on farms (i.e. farm attacks) in some provinces. This state of affairs was not the fault of CIAC, because they had to work with the information on the Crime Administration System. The problem was probably the result of cases being registered incorrectly on the CAS, but unfortunately the Committee did not have enough time to investigate this matter further. The result is that, although the Committee is fairly confident about the comparative figures for the Eastern Cape, it is not quite satisfied with the comparative figures for farm attacks in the other four provinces, and they should be considered with this proviso in mind.

The criteria used in this comparative study are the following:

- The time of day that the attack occurred.

- The place of first contact between attacker and victim.

- The method used by the attacker to approach the victim.

- The method of entry into the house.

- The weapons that were used by the attacker.

- Whether the victim was injured.

- Whether the victim was tied up.

- The items stolen.

- The race of the victim.

- The age of the victim.

- The number of attackers.

- The race of the attacker.

- The personal particulars of the attacker.

- How the case was finalised.

Note that in a few of the farm attacks as well as the house robbery cases some of the information needed for the comparisons is not known. Those cases are ignored and the percentages are calculated on the remaining cases only. Since direct comparisons cannot be made, it will serve no purpose to give the actual figures and the ratios are rather expressed as percentages.

Time of the attack

Research done elsewhere indicates that the days of the week on which farm attacks are likely to occur are quite unpredictable.6 (There is a slight increase on Fridays, possibly because it the usual day for the payment of wages.) The research into house robberies has revealed exactly the same random pattern. Similarly, as far as the month of the year is concerned both farm attacks and house robberies have a fairly even and similar distribution throughout the year.7 It would therefore serve no purpose to try and draw any comparisons in this regard.

However, this comparative study reveals a significant difference between the time of day on which the farm attacks and house robberies mostly occurred, especially in the Eastern Cape. (See Table 37.) For the purposes of this comparison the day is divided into periods of four hours each, starting at midnight. The periods during which the farm attacks in the Eastern Cape were most likely to occur were in the mornings between 08:00 and 11:59 (29.0%) and evenings between 20:00 and 23:59 (23.6%). The periods during which most house robberies were committed were in the evenings between 20:00 and 23:59 (32.3%) and at night between 00:00 and 03.59 (29.2%). This difference is not quite as pronounced in the case of the other four provinces.

One would have liked to compare specifically the percentage of farm attacks and house robberies which occurred during the day and at night, but unfortunately the times used in the study of house robberies do not make that possible. The nearest approximation that can be used is the period from 08:00 to 19:59 for daytime and from 20:00 to 07:59 for the dark hours. This shows that, in the Eastern Cape, whereas some 50.5% of farm attacks were carried out between 08:00 and 19:59, only 29.2% of house robberies took place during those hours. In the other four provinces, fully 54.6% of the farm attacks occurred during the ‘day’, as opposed to only 33.1% of the house robberies.

Fully half of the farm attacks therefore took place during the ‘day”, whereas two thirds of the house robberies occurred at ‘night’. This difference in the likely time of the attack may be due to the fact that in an urban setting an attack at night is less likely to draw attention from outsiders. Furthermore, during the day many of the security measures introduced by farmers are disabled: the alarm systems are switched off, the doors and security gates remain unlocked, etc. It does suggest, however, that farm residents and employees should not be less on their guard during daylight hours at all.

Place of first contact between attacker and victim

Obviously only cases where the attacker entered or attempted to enter the house were taken into account. Where the first contact between the attacker and the victim took place inside the house, that would typically have been where the perpetrator gained entry by breaking in or by means of a door or window left open or unlocked. Where the victim was confronted outside the house, he or she would typically have been forced at gunpoint or otherwise to take the robber inside to enable him to ransack the house, or the would-be attacker would have been allowed inside on some pretext.

In 47.3% of the 91 farm attacks in the Eastern Cape this initial contact took place outside the home, while only 22.7% of the 66 house robberies started outside. There is therefore a significant difference between the two in this respect. This may be due to various factors, e.g. the fact that it is not as easy in an urban environment to carry out a robbery outside in the yard where neighbours and other persons may notice it. The farm attacker may also regard the security systems protecting the farmhouse as too formidable, whereas in the less well-to-do black communities this may not present the same problems. The farm attacker may also be uncertain about the type and degree of resistance he may encounter inside the house and may prefer to meet the victim out in the open. (See Table 39.)

In the other four provinces, however, this difference is not nearly as pronounced: 68.8% of the farm attacks commenced inside the house, as did 72% of the house robberies. This discrepancy is not easy to explain. There is reason to believe that the Eastern Cape figures are not far off the mark. In the recent study by the Eastern Cape office of CIAC, it was found that of all farm attacks during 1999 (including murder, rape and other types of cases not taken into account in this comparison) some 49.3% commenced outside the house or building, and in 2000 some 47.9%.8 This correlates very accurately with the figures given above for the 91 cases. Furthermore, according to the provisional figures for all the farm attacks in the country for the year 2001 supplied to the Committee by CIAC, 49.2% started outside.

Be that as it may, it is clear that a farm resident is almost as likely to be attacked outside the house as inside. This is very significant when safety measures are considered.

Method of approach used by the attacker

In most cases, both in farm attacks and house robberies, the victim was surprised and overpowered by the attacker, either outside or inside the house. In some cases the attacker approached the victim on some pretext, i.e. pretended to be an innocent outsider. In the case of the farm attacks that would typically have been someone who pretended to want to buy milk, sheep or some other farm produce. In the case of house robberies it would typically have been someone knocking on the door posing as a person in authority such as a policeman, or pretending to be looking for someone.

The analysis is shown in Table 40. In the Eastern Cape a noticeably greater percentage of attackers, viz. 21.2%, used some pretext as a method of approach for house robberies than was the case with farm attacks, where this percentage was 13.2%. On the other hand, the average percentages for the four other provinces show a different pattern: in 18.2% of the farm attacks some pretext is used to enable the perpetrator to approach the victim, whereas only 13.9% of the house robbers made use of a ruse. Again, this discrepancy is difficult to explain.

Method of entry into house

Entry to the house by the attacker can be by physically breaking in, by gaining entry through an open or unlocked door or window, by forcing the occupant to allow him inside, or by being allowed in freely by the occupant. (It should be noted that in law it is housebreaking where a closed door or window is opened to gain entry, even if it was not locked, but this is ignored for the purposes of this study.)

In the Eastern Cape farm attacks considered, the house was broken into in 27.5 % of the cases, in 25.3% of the cases the attackers entered through open or unlocked doors or windows, and in 36.3% of the cases the attackers forced the victims to let them in. In only one instance did the occupant freely allow the attackers inside on some pretext. In quite a few cases, however, the attacker knocked on the door and then forced his way in once the door was opened. In 9.9% of the cases the attackers did not gain entry to the house, e.g. because they were repelled by the victims. (See Table 41.)

For the Eastern Cape house robberies the mode of entry in three cases is not known. Of the remainder there was a break-in in 42.8% and unobstructed entry in 15.9% of the cases. In only 11.1% of the cases the attacker(s) forced the victim to allow them inside, while in no less than 20.6% of the cases the culprit was allowed inside on some pretext and with the consent of the occupier. In 9.5% of the cases the attacker did not gain entry to the house, a figure similar to that of the farm attacks.

The much greater percentage of victims forced to let the attacker inside during farm attacks as opposed to house robberies, again is not easy to explain. It correlates with the figures for the place of first contact and, as indicated above, the opportunities for some ruse are greater in an urban setting than on a farm. It may also be that racial or class prejudice makes it unlikely that a farm attacker (mostly black, unemployed and uneducated) will be allowed inside the farmstead of a perhaps conservative white farmer.

In the other four provinces this difference is not as pronounced. Nevertheless, 27.5% of the farm attack victims let the perpetrator in under duress, whereas 19.8% of the house robbers forced the victim to let them inside.

Weapons used by the attacker

In the 91 Eastern Cape farm attacks firearms were used on 45 occasions (49.5%). (See Table 42) In 54 or 59.3% of the attacks knives or other types of weapons were used. (This means that in 8 cases firearms were used in conjunction with other weapons.) This is surprising, especially in the light of the perception that most farm attacks are military style operations and are carried out by means of firearms.

Equally surprising is the fact that in the 66 cases of house robberies firearms were used 63 times or in 95.5% of the cases, while in 14 cases (20%) other weapons were used. (On 11 occasions, therefore, both were used in conjunction.) It is interesting to note that only three of the farm attack victims were actually shot, although on several occasions shots were fired at victims but missed. Only one of the house robbery victims was shot, although it is not known whether shots were also fired which did not wound anyone.

The position with the farm attacks in the other four provinces is quite different: in no fewer that 94.8% of the cases were firearms used. For house robberies the figure is the same as in the Eastern Cape. This enormous difference between the Eastern Cape and the other four provinces is very difficult to explain.

Victims injured

As indicated above, all cases where someone was killed are ignored in this comparative study, even if there were other victims in the same attack who were not injured or only sustained injuries. This is somewhat unsatisfactory, because when the attacker is prepared to kill one victim, he will certainly also be prepared to use serious violence against the others. In fact, it is often found during farm attacks that, when one of the victims is killed, the other victim or victims may be seriously injured. One has to assume, however, that the same applies to house robberies.

There were 143 victims in the 91 cases of farm attacks under consideration. Of those 29.4% were injured. (According to the provisional figures for 2001released by the CIAC, 2003, of the 1398 victims of all farm attacks countrywide, some 484 (34.6%) were injured. The injury rate in the Eastern Cape cases therefore is somewhat lower than the national average.)

There were 80 victims in the 66 cases of house robberies investigated. The fate of only 75 victims is known, however, and of those 16% were injured. (See Table 43.)

In the other four provinces 19.4% of the 124 victims of farm attacks were injured. There were 377 victims of house robberies, and of the 340 victims whose fate is known, 11.5% were injured.

It is clear from the above that a victim was almost twice as likely to suffer injuries during a farm attack in the Eastern Cape than during a house robbery. (One is justified in ignoring the five house robberies where the fate of the victims is unknown, since it is more likely that it would have been noted if they had been injured, rather than the other way round.) In the other four provinces there was also a significantly greater chance of victims of farm attacks being injured.

It is also possible to compare the type of violence used in terms of the injuries inflicted. (See Table 44.)

The comparisons for both the Eastern Cape and the other four provinces indicate that the type of violence used by the attacker proportionally does not vary significantly, except that a greater proportion of farm attack victims sustained bruises, which by nature are a less serious type of injury. This may well be attributable to the relatively large number of elderly farm residents being attacked, who may bruise easily. On the other hand, two of the farm victims were strangled, one of whom actually lost consciousness, a fate which befell none of the house robbery victims

In terms of the likelihood of being injured, therefore, though not in terms of the severity of the injuries, the conclusion that farm attacks are more violent that house robberies seems to be justified.

Victims tied up

It is doubtful whether the information concerning victims being tied up during the course of farm attacks is very reliable, because the Committee mostly had to rely on the cryptic information on the NOCOC database, which does not always indicate whether the victims were tied up or not. In the case of house robberies the information may be more accurate, since the individual police dockets were perused.

If anything, therefore, it has to be assumed that the number of victims tied up during farm attacks may be more than indicated. Nevertheless, it seems that of the 143 victims in the farm attacks in the Eastern Cape at least 32.2% were tied up, whereas in the case of the 80 victims in house robberies, only 3.8% were tied up. (See Table 45)

This pattern repeated itself in the other four provinces: About 25.8% of the farm attack victims were bound, while only 8.3% of the victims of house robberies in the other four provinces were tied up.

This phenomenon is difficult to explain. It may be due to the fact that during a farm attack the culprits need more time to escape than is the case with house robberies in an urban environment, where the culprits can make a getaway more easily. It may also be part of the intimidation process because of the feeling of helplessness that being tied up creates. Case studies have shown that very often victims are assaulted after they have been tied up, e.g. to reveal the whereabouts of money or firearms.

It should be noted that, apart from victims of farm attacks being tied up, quite a substantial number were locked up in a room while the house was being ransacked. Although there are one or two examples where the victims managed to escape, this was usually impossible because of burglar bars in front of the windows. (Obviously the attacker would not have locked up the victim in a room without burglar bars.) It is not known whether the same happened during the house robberies.

Items stolen

During the 91 farm attacks in the Eastern Cape some 63 firearms were stolen in 31 of the cases (34.1%). Usually the farmer only has one or two weapons, but on one occasion six firearms were taken and on another occasion five. Some security guards were also robbed of their firearms. During a farm attack the assailants would usually demand to be given weapons and money and for the safe to be opened. (In one remarkable case the one attacker also wanted to take the firearms in the safe, but he was prevented by his accomplice, who reminded him of the fact that they had come specifically to rob money.) During the 70 house robberies firearms were stolen on only 4 occasions (6.1%). (It is unknown how many firearms were taken.) Many more firearms were therefore stolen during the course of farm attacks than was the case with house robberies. The explanation probably is that in an urban setting there are fewer firearms, especially amongst the less well-to-do and black communities. In the other four provinces fewer firearms were stolen on the farms, but still many more than during the house robberies. (See Table 46.)

Vehicles were stolen in 10 (11%) of the farm attacks in the Eastern Cape, while the figure for house robberies is 3%. In the farm attacks some of the vehicles were used to get away, and were later found abandoned. (It is interesting to note that of the 29 vehicles stolen during all farm attacks in the Eastern Cape in 1999 and 2000, no fewer than 25 were recovered.) In a few cases the attackers could not drive and crashed the vehicles. In the other four provinces vehicles were stolen in 31.2% of the farm attacks.

In the case of house robberies, both in the Eastern Cape and the other four provinces, money was stolen in two thirds of the cases, while this was a less important target during the farm attacks.

In 61.5% of the farm attacks in the Eastern Cape other items in general were also stolen. Cellular telephones and jewelry were especially sought after. In the majority of house robberies items such as cellular phones, jewelry, clothing, radios, etc., were also stolen, but the available figures do not allow percentages to be calculated.

Finally, it should be noted that in no fewer than 18.7% of the farm attacks in the Eastern Cape, nothing at all was stolen. At first sight this would tend to confirm the view that the attacks were carried out with other motives than robbery. Upon analysis, however, it turned out that there was a rational explanation: in almost all these cases the attacker or attackers were thwarted by the victims who resisted or by some other intervention. (Three attackers were actually killed. Two were shot dead and one was fatally stabbed by the wife of the farmer with whom he was engaged in a life and death struggle. In one case the victims, two domestic workers who were bound, say that the attackers were specifically looking for weapons, and when they could not find any they simply left.)

Unfortunately, this calculation could not be made for farm attacks in the other four provinces or for the house robberies, whether in the Eastern Cape or elsewhere, because the information was not available.

Race of the victims

In the Eastern Cape farm attacks 69.9% of the victims were white, 25.9% were black and 4.2% were coloured. There were no Asian victims. Thirty nine of the 43 black or coloured victims of farm attacks were attacked while on duty as employees of the farmer, such as domestic workers, farm hands or security guards. For house robberies in the Eastern Cape the position is reversed: 76.3% were black, 18.8% were coloured or Asian and only 5.0% were white. No doubt this difference is largely due to the fact that 80.3% of the house robberies investigated took place in townships or informal settlements, which are inhabited almost exclusively by black people. (Table 47)

The racial composition of the victims of farm attacks in the other four provinces differ considerably, however: no fewer than 47.6% of the victims are given as black, with only 51.6% being white. It is difficult to explain this difference. For farm attacks in general, committed during 2001, the provisional figures of CIAC indicate that of the 1398 victims 61.6% of the victims were white, 33.3% black, 0.7% coloured and Asians 4.4%. (Almost all the coloured victims came from the Eastern Cape.) If one looks only at the four provinces in question, in all types of farm attacks 54.5% of the victims in Limpopo were black, 47.6% in Mpumalanga, 28.2% in the Free State and 24.8% in North West Province. This, however, can only partly explain the higher proportion of black victims in the four provinces. Another probable reason may be that some house robberies on farms may not have been registered as farm attacks, for various reasons.

It should be noted, however, that of the 100 white victims in farm attacks, 42% were injured, whereas of the 43 black or coloured farm attack victims, only one (2.3%) was actually injured. (The one black man injured was the farm manager.) On the other hand, about the same proportion were tied up: 14 (32.6%) of the black or coloured victims as against 34 (33.7%) of the white victims. The typical situation in farm attacks would be for the domestic workers (usually black or coloured) to be overpowered and tied up while the owner is absent. The attackers would then ransack the house. Sometimes they would wait for the return of the (usually white) owner, who would then be assaulted, perhaps to open the safe under some duress.

The comparison therefore indicates that a white victim was far more likely to be injured during a farm attack in the Eastern Cape than a black employee or other resident on the farm. (This does not mean that black people are not the victims of violent crimes on the farms. Research, and the experience of most investigating officers and prosecutors, have shown that in general black farm residents are far more likely to suffer harm as a result of violent crimes than whites. Those are mostly crimes that fall within the definition of social fabric crimes, however. This would typically be cases where persons get stabbed during a drunken brawl. Women and young girls are often the victims of domestic violence or rape.)

Age of victims

In the case of the farm attacks in the Eastern Cape the ages of some 139 victims are known. Of those 3.6% were under 20 years of age, 30.2% were between 20 and 39 years, 19.4% were between 40 and 59 years, 39.6% were between 60 and 79 years and 7.2% were 80 or older. Persons of 60 and over therefore make up almost half of the victims (46.8%). (See Table 48.)

In the case of house robberies there is a very big shift towards younger victims. Most (54%) were between 20 and 39, and only 5.4% were 60 and over. In the other four provinces the average ages of the farm attack victims are slightly lower, but the difference between them and house robbery victims is equally so pronounced.

It is therefore clear that the victims of the farm attacks tended to be much older than the victims of the house robberies. There may be several reasons for this huge difference. One may be that the average life expectancy for white persons (the majority of farm attack victims) is longer than for black people, who make up the majority of victims of house robberies in an urban setting. Another reason is that farm attackers tend to search out aged victims from whom less alertness and resistance may be expected. (It should be mentioned, however, that one of the black farm attack victims was 70 years of age, while one coloured victim was 85, but those were exceptions.)

Number of attackers

At least 234 perpetrators were involved in the 91 Eastern Cape farm attacks. The precise figure is not known but is likely to be more because all the attackers are not always observed by the victims. The average number of attackers per case therefore were at least 2.6. There was one attacker in only fourteen cases, and the largest number involved in any single attack were nine.

At least 174 perpetrators were involved in 66 house robberies in the Eastern Cape, at an average of also 2.6 per case. In some cases the exact number is also unknown, so the figure is also likely to be more. In ten cases there was only one perpetrator, and the largest number involved in a single case were ten. (See Table 49.)

The perpetrators in the house robberies investigated in the other four provinces averaged 2.4 per case. The farm attackers averaged 2.8 per incident.

The number of attackers are therefore more or less the same in all instances, the typical group numbering two or three.

Race and gender of the offenders

Both in the case of farm attacks as well as house robberies in the Eastern Cape the perpetrators were either black or, in a few instances, coloured. There were no whites or Asians involved. There were 2 white and 3 coloured perpetrators involved in the house robberies investigated in the other four provinces. There were four whites involved in the house robberies on the farms in the other four provinces. (See Table 50)

One female was possibly involved in one of the farm attacks in the Eastern Cape. (She was part of a group that went to the farm under pretext of wanting to buy cattle, but did not take part in the robbery itself.) In the other four provinces there were two females involved. As for house robberies, only male perpetrators were noticed. The gender of a few is unknown, but it is reasonable to assume that they were probably all male. In the other four provinces, however, there were 7 female perpetrators.

Personal particulars of the offenders

Because such a large number of house robberies remain unsolved, the personal particulars of most of the offenders, other than their gender and race, are largely unknown. This applies to their ages, levels of education and occupations. (See Table 51)

Of the 174 house robbers in the Eastern Cape, particulars of only about 27 are known. Ten of them were between 15 and 19 years of age, 15 were between 20 and 29, and 2 were between 30 and 39. Because of the relatively small sample, the proportions calculated for for each age group may not be very accurate.

Two had never attended school and only one had matriculated. All of them, except for one student, were unemployed. In the other four provinces most offenders also seem to be between 20 and 30 years of age and most of them were also unemployed.

Although farm attack cases have a much higher arrest rate, the database that the Committee used did not have the particulars of the offenders readily available. However, the Committee has made a study of the typical personal profile of farm attackers in general and it is clear that there is a remarkable correlation with the profile of house robbers described above. 9

Disposal of cases

The NOCOC database for farm attacks does not have sufficient information on the success rate for solving and prosecuting farm attacks, because follow-up information on later developments is not always added to the database. It is generally accepted, however, that the success rate for finding the criminals in farm attack is relatively high.10 CIAC office in the Eastern Cape undertook a survey of the results of 142 case dockets opened for farm attacks in 1999 and 2000. Of those 77 cases had been disposed of, with the following results: 53.2% had gone undetected or had been withdrawn, in 42.9% of the cases there had been a conviction and 3.9% had resulted in an acquittal. (See Table 52.)

The success rate for solving the house robberies in the Eastern Cape, however, was very low. Of the 66 cases some 92.4% went undetected or were later withdrawn because of lack of evidence. Only 6.1% of the cases were successfully prosecuted, while 1.5% resulted in an acquittal.

In the other four provinces, the success rate for house robberies is about the same as for the Eastern Cape. Farm attack prosecutions, however, are in a much worse position, with no fewer than 77.3% of the cases not being prosecuted at all. Only 17.3% resulted in a conviction.

The figures for disposing of house robbery dockets are simply appalling, with 92.4% of the cases never even brought to trial. It can be accepted that more serious cases, where murder or rape is involved, will receive greater priority and that the success rate may be higher. In comparison farm attack cases are much more likely to end up in court, with a good conviction rate.

No comments:

Post a Comment